For more information on Pakistan (1960-1969), see:

https://www.alternatehistory.com/fo...rnative-cold-war.280530/page-22#post-11230254

===

Yahya Khan, final military leader of Pakistan, who saw the secession of Bangladesh

The Pakistani defeat in the 1965-1967 Bharati-Pakistan War fundamentally destabilised the emerging political order in Pakistan. The military leaders of the country had been severely discredited by their failure to secure the borders of the fledgling nation. Ayub Khan was replaced by Yahya Khan, who had commanded the 7th Infantry Division in the Bharati-Pakistan War. Despite his incompetence as a military commander, he was promoted by Ayub Khan to Commander-in-Chief of the Pakistani Army. Yahya Khan took the mantle of political leadership after Ayub Khan's fall from grace, but proved as incapable as a civilian politician as he had been as a general. He immediately placed the country under martial law, and became known for his alcoholism and whoring. Despite these personal and professional failings, he was expected by anti-Ayub political factions to transition effectively to a democracy. Already difficult enough, these challenges were compounded by the regional divide between East and West Pakistan, which was inflamed by an uncertain constitutional relationship between the two areas. Whilst East Pakistan was the larger of the two Pakistans in population size, and was more politically-united through representation by the Awami League, West Pakistan was the traditional seat of power and produced most of the Pakistani military and business elite. Yahya Khan responded to these challenges by abolishing the 'One Unit' system, which had abolished the provinces and caused unrest in the various regions since its introduction in 1955. He also made attempts to redress the regional imbalance, leading to the seizure of a greater number of seats in the National Assembly by the Awami League. Rather than appeasing the Bengalis, in fact this confirmed their accusations of prior political marginalisation, whilst threatening the West Pakistani representatives with legislative irrelevancy.

By 28th July 1969, Yahya had established a framework for a set of democratic elections to be held in December 1970. In the 1970 general election, the Awami League won a total mandate in East Pakistan, whilst the Pakistan People's Party (PPP) of Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto won a majority in all the provinces of West Pakistan. The Awami League won 160 seats, whilst the PPP secured 81 seats and the conservative Pakistan Muslim League (PML) held 10. The fundamental split between the East and the West of the country was now unquestionable. The PPP and Awami League began bilateral negotiations in order to form a coalition government, but hit an impasse when Bhutto refused to endorse the 'Six Points' of the Awami League, which sought maximum devolution for East Pakistan, including a separate currency and an autonomous military force. Frustrated by the political deadlock, Yahya Khan ordered the commencement of Operation Searchlight in support of the PPP, which would involve the seizure of towns in East Pakistan and the eradication of political opposition. Yahya Khan is quoted himself as saying "kill three million of them [Bengalis] and the rest will eat out of our hands" at a conference in November 1971. Yahya Khan claimed that the operation was in response to the killing of 300 Biharis (West Pakistanis) in Chittagong in March 1971 by Bengali mobs. The overall commanders of the Pakistani military resigned in protest to the operation, which went ahead anyway. In the run-up to the operation, Bengali military forces were scattered and officers were put on leave or sent to less sensitive areas in order to ensure a greater likelihood of success. On 25 March, Operation Searchlight commenced. Pakistani special forces commandoes captured Awami League leader Sheikh Mujibur Rahman (Mujib) almost immediately, and almost all of the League's leadership was captured by the 29th. The 22nd Baluch Regiment, which was charged with security near the East Pakistan Rifles (EPR) HQ, subdued the largely disarmed and disorganised EPR remnants during the night of the 25th (most of the EPR units had been deployed near border posts). Pakistani forces then secured Dhaka University, killing unarmed students and professors, before moving on to Hindu areas, where troops continued killing innocents. The 2nd EPR wing began to counterattack on the 26th, but after some initial success, the Pakistanis were able to halt and then subdue the Bengali resistance in Dhaka. The attack on Dhaka was followed by the seizure of Chittagong. Despite outnumbering the Pakistanis, the Bengalis failed to take the offensive as a result of disagreements between the EPR commanding officers. The Pakistani Army and Navy mounted a joint attack on the city. Bengali organised resistance collapsed and thousands of civilians were slaughtered.

By the 10th of April, the Pakistani Army was in possession of Dhaka, Rangpur-Saidpur, Comilla, Chittagong and Khulna. They had lost control of Rajshahi, Sylhet, Pabna, Dinajpur, Mymenshing and Kushtia to the EPR. The brutality of the Pakistani army in Operation Searchlight and subsequent campaigns provoked strong opposition from the Bengalis, who flocked to the

Mukti Bahini ('Freedom Fighters', MB), a Bengali guerrilla movement that sought to liberate East Pakistan from West Pakistani occupation. The Pakistanis were surprised at the stiff Bengali resistance, their dismissive attitude towards the Bengalis symptomatic of the racist views held of Bengalis by many West Pakistanis as spineless and submissive. Operation Searchlight also suffered from its ambitious scope, and the objective of pacification by April 10th was not achieved. Despite Pakistani control over the major cities and airfields, the inability of the Pakistani army to crush Bengali resistance would prove the catalyst for the eventual dissolution of Pakistan in its entirety. The scattered Bengali forces were left with few arms and supplies, despite having a large recruitment pool, and were ordered by

Mukti Bahini leader M.A.G. Osmani to fight autonomously, whilst Awami League political leaders sought support from Bharatiya. As would be expected, the poorly-trained MB fighters were incapable of besting the Pakistani Army in conventional combat. They also proved rather ineffective at fighting guerrilla war, with their ambushes of Pakistani convoys doing little more than delaying the Pakistani advance, as West Pakistani units fanned out from the towns to seize large swathes of the countryside using aggressive hunter-killer air cavalry tactics. The Pakistani Army also mobilised a number of paramilitary formations, most notably the

Razakars, largely composed of collaborationist Bengalis, who were often guilty of the more heinous atrocities against Bengali villages. Several Islamist militias also supported the Pakistani Army against the MB, but were of mixed effectiveness.

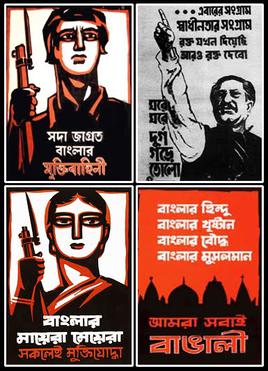

Mukti Bahini propaganda posters

The Bengalis' saving grace came in the form of Bharati intervention. Whilst the Bharati government and the Awami League were strongly opposed ideologically, the Bharatis sought to weaken Pakistan and improve their international diplomatic position through the liberation of East Pakistan. The international community had become aware of the plight of the people of East Pakistan, and a number of benefit concerts were held to send badly-needed aid. The intervention was a propaganda coup for the Bharati government, which could dismiss claims of hostility towards Muslims through the intervention, as well as making a convincing claim that the Pakistani government has been more oppressive to the Muslims they are supposed to protect than the Bharati Hindu nationalists. Whilst such claims obscure the situation within Bharatiya itself, it nevertheless improved the view of Bharatiya in the West. Realising the undesirability of association with Yahya Khan's government, the United States cut ties with Pakistan and began developing a close relationship with the fiercely anti-Communist Bharati government which had been courting them for years. The intervention itself occurred after a preemptive strike was launched by Pakistani Air Force warplanes on Bharati Air Force bases in December 1971. Bharati units, including troops which had participated in the Tibetan campaigns, poured into East Pakistan, overrunning the country with the support of auxiliary MB units. The Bharatis largely bypassed fortified areas, surrounding them and forcing the Pakistani forces into a surrender, which was signed on the 16th. Most of the United Nations voted in favour of the recognition of the new nation of Bangladesh, although this was vetoed by the Chinese, who still maintained a close relationship with Pakistan.

With the surrender of East Pakistan and the creation of an independent Bangladesh, the position of Yahya Khan back in Pakistan became untenable. Street demonstrations by outraged citizens became commonplace, and rumours abounded in Karachi of an imminent coup d'etat against Yahya Khan. In order to prevent further unrest, Yahya Khan handed the reins of power over to PPP leader Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto on December 20th 1971. Pakistan was facing a political crisis unlike it had ever faced before. Emboldened by Bangladesh's independence, Pashtun, Baloch and Sindhi nationalists began to push for their own states. With the very existence of the country at stake, Bhutto began a military crackdown against separatists. Bhutto embarked on an ambitious reform programme, promulgating a new constitution in 1973 and engaging on economic reform driven by nationalisations and improvement of conditions for workers. Unfortunately, the nationalisations didn't operate as effectively as expected, largely because many of the nationalised businesses were too small to be effectively operated as state enterprises. His education policy was controversial: whilst he established thousands of new schools, he also abandoned Western education in favour of solely domestically-produced academic materials. A particular obsession of Bhutto's was with physics, which he strongly promoted as a means to produce the intellectual resources necessary to produce a nuclear weapon, a priority that became more urgent after the detonation of Bharatiya's first atomic weapon in 1974, the so-called "Parashurama" test. Bhutto also began to articulate a programme for land reform, which was to empower the Sindhi masses, despite upsetting the feudal landowners. He was toppled from power before this programme could achieve significant results. Irritated at America's abandonment of Pakistan, Bhutto turned to the Soviet Union as an alternative superpower patron. The Soviets, eager to gain direct access to the Indian Ocean, participated in a number of development projects, including the establishment of Pakistan Steel Mills in 1972 and the construction of Port Qasim in Karachi.

Suppressing separatist movements still remained, however, the primary concern for Bhutto and his government. Rising unrest in Balochistan province in the country's southwest had prompted Bhutto to dismiss two provincial governments within two months, arrest to Balochistani chief ministers, two governors and dozens of parliamentarians. He also banned the National Awami Party, which had significant support within Balochistan, and charged everyone with high treason to be trialled before a court stacked with handpicked judges loyal to Bhutto. As a result of Baloch outrage with these actions, the insurgency lead by tribal

sardars (chiefs) began to intensify. In response, Bhutto ordered the military to suppress the Baloch nationalists in January 1973. A month later, an arms cache was discovered in the UAR embassy in Karachi[169]. The Pakistan Navy began a blockade of the Balochistani coast, intercepting UAR attempts to smuggle arms. However, they proved unable to prevent aid trickling down from Afghanistan to the Baloch tribal warriors. Wary of the Baloch insurgency in Pakistan supporting the Baloch separatists in Iran, the Shah also providing air support for the Pakistani Air Force. The two air forces pummeled the mountain hideouts of the Baloch fighters. Nevertheless, the Baloch kept fighting until they were granted independence in the wake of Pakistan's collapse. In the North-West Frontier Province, the situation was more complicated. Whilst Pashtun nationalists fought for an independent Pashtunistan, their co-ethnics in the Afghan government would provide only limited support. This was largely as a result of internal security issues caused by the support of Islamist

mujahideen such as Gulbuddin Hekmatyar and Ahmad Shah Massoud by Bhutto's government. Nevertheless, as this support began to wither up with Pakistan's fall, the Afghans would take advantage of the situation wholeheartedly.

Sher Mohammad Marri (in sunglasses) and some of his Baloch guerrillas

Concerned with the increasing Soviet presence in Pakistan, the CIA and US State Department officials began to make encouraging overtures to Bharati leaders. With the death of M.S. Golwalkar in 1973 and his succession by Balasaheb Deoras, the relationship between the United States and Bharatiya strengthened rapidly. Deoras agreed to an attack on Pakistan, which was to result in the annihilation of Pakistan and the fall of the Bhutto government, in return for generous aid grants, a favourable trade relationship, and the assertion of Bharati dominance over Sindh, the most economically-valuable part of Pakistan. On 5 June 1975, two years to the day after M.S. Golwalkar passed away, Bharati troops crossed the border into Pakistan. Falsely claiming that Bhutto was the patron of the numerous Communist insurgencies active within Bharatiya, Deoras had ordered a full-scale invasion. Denounced by many of the nations of the UN, but supported by the United States, the invasion brushed aside Pakistani resistance. Attacking along three axes, the Bharati forces, armed with heavy artillery, tanks and US-made warplanes such as the F-4 Phantom II, overwhelmed the Pakistani forces at every part of the front. The Pakistani tank forces were gutted in the Thal Desert as the Bharatis made the most of their air superiority after annihilating Pakistan's small interceptor force of Shenyang J-6s. A smaller central column pushed through the Cholistan desert, whilst the most powerful thrust pushed south and seized Karachi. The Pakistani Navy was bettered in a number of sorties by the Bharati Navy, and a blockade was instituted. Within two weeks the Bharati forces were in control of the majority of the country. Baloch tribals seized Gwadar and even Quetta, whilst Daoud Khan participated in a small, undeclared war, sending in Afghan troops disguised as tribal fighters, taking a page out of Pakistan's own playbook in the 1947-9 war. These troops, with assistance from local, authentic tribal warriors, occupied Peshawar and proclaimed the 'State of Pashtunistan'. Bhutto and his government escaped to Aden, where they were initially determined not to surrender. However, after some time, Bhutto caved, and signed an instrument of surrender. Deoras announced the dissolution of Pakistan, announcing that no longer would the peoples of the area be shackled to such an artificial concept of nationhood. The independence of Balochistan and Pashtunistan was confirmed. A mere month later, after a loya jirga in Peshawar, Pashtunistan committed to union with Afghanistan. The incorporation was complete by September. Balochistan was given independence as a constitutional monarchy, with the Bharatis demanding that the last Khan of Kalat, Ahmad Yar Khan Ahmedzai, sought be named Khan of Balochs. This was intended to counteract the influence of the leftist Baloch politician Khair Bakhsh Marri and Marxist guerrilla leader Sher Mohammad Marri. This coalition would remain uneasy but stable through the rest of the 1970s, as Ahmad Yar Khan Ahmedzai kept largely aloof from politics, except to step in as a moderating influence. Of the post-Pakistani states, the only one to arise not out of an armed struggle, but purely out of a domestic politic movement was Sindhudesh. Sindhudesh arised out of nationalist agitation in Sindh province as a result of the dominance of the Punjabi and incoming Urdu-speaking Muhajir peoples who had fled India during partition. Feeling marginalised in their own home province, Sindhi nationalists flocked around G.M. Syed, who positioned himself as the preeminent Sindhi nationalist intellectual, proposing an independent Sindhi homeland in 1972. Publishing books with titles such as

Now Pakistan Should Disintegrate and

Sindhu Desh - A Nation in Chains, and establishing an independence organisation, the

Jeay Sindh Mahaz (JSM), Syed would become known as the 'father of the nation' once he became the President of Sindhudesh after his installation by the Bharatis. The extent to which he facilitated Bharati domination of the Sindhi economy would prove controversial in later histories, with arguments over whether or not he was their willing patron, or that he simply recognised his vulnerability vis-a-vis the Bharatis and sought to appease them for the sake of his own people. Nevertheless, he engendered criticism in his failure to even attempt to break the power of the Sindhi aristocracy, who became the primary agents of Bharati imperialism, according to Marxist historiography.

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, Bangladesh's 'father of the nation'

After being released from captivity by Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto in the aftermath of Yahya Khan's downfall, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman assumed the provisional presidency of Bangladesh and became the country's first Prime Minister. The MB and other militias were combined to form the Bangladeshi Army, which took over protection of the nation from Indian forces after their withdrawal. Despite the avowed secularism of the Awami League and the Bangladeshi government, Mujib began to move closer to political Islam as a means to shore up his support, aware that the Communists on the far left were opposed to his rule. Mujib declared a common amnesty to shore up his support amongst the Islamic right, aware that many of the Bengalis who had fought on the Pakistani side had done so out of pan-Islamist sentiment. Mujib had the provisional parliament draft a new constitution, which incorporated the fundamental principles of "nationalism, secularism, democracy and socialism", which would be referred to amongst Bangladeshis as "Mujibism". Mujib commenced widespread nationalisation, whilst pushing through land reform intended to bring millions of tenant farmers out of abject poverty. He also initiated nationwide education, sanitation and infrastructure programmes to modernise the country. Proclaiming a constitution in 1973, and holding elections shortly thereafter, Mujib won a sweeping victory and the Awami League remained in power. The Awami League government continued to tackle the severe challenges facing the ravaged country, including attempts to provide homes for 10 million refugees displaced during the Liberation War, as well as combating the 1974 famine, which killed 27,000[170]. Mujib managed to build a constructive relationship with both superpowers, and received generous aid from Eastern European, Japan and the UAR. Partially as a result of these policies, and partially out of dissatisfaction with the government's response to the 1974 famine, a Maoist offshoot of the Bangladesh Chhatra League (the Awami League's student wing), known as the Jatiya Samajtantrik Dal ('National Socialist Party', JSD) began an armed insurrection. The JSD's armed wing, the

Gonobahini ('People's Army), attempted an attack on the Home Minister Mansur Ali's residence, which was repulsed. They then held a major rally blockading the residence. Stirring the crowd into a frenzy, the JSD engaged in street battles with riot police. The

Jatiya Rakkhi Bahini (RB), which was formed as a government death squad to counter the JSD, arrived on the scene and began to fire live bullets into the crowd, resulting in the 1974 Ramna Massacre, killing at least 40 protestors, many of whom were lying on the ground already. Faced with this brutal response, the JSD was driven underground, where it remained an insignificant political force. The only legal political force in Bangladesh was the Bangladesh Krishak Sramik Awami League (BaKSAL), which was comprised of the Awami League, the Communist Party of Bangladesh, the National Awami Party and the Jatiyo League after the fourth amendment of the Bangladeshi Constitution in June 1975. Despite this monopolisation of the political party system, Mujib's government started to suffer from dissatisfaction with his nepotism, preoccupation with national over local problems, and what was generally seen as a lack of political leadership brought on by post-liberation complacency. The industries which he had nationalised were performing poorly, and the expensive social programmes introduced could not be supported by a dwindling economic base. The

Rakkhi Bahini, who had immunity from prosecution, engaged in widespread killing of political opponents. The RB has been accused of killing as many as 40,000 dissenters. Facing growing opposition, Mujib declared martial law in late 1974.

On 15th August 1975, Mujib was assassinated in a CIA-backed coup led by junior military officers and headed by Khondaker Mostaq Ahmad, a colleague and friend who had become disillusioned with Mujib. Ahmad became President of Bangladesh and purged much of the senior pro-Mujib leadership, but was himself overthrown by a coup on November 6th by Khaled Mosharraf and Shafaat Jamil. A day later, Mosharraf was killed by a mutiny of left-wing non-enlisted personnel led by JSD leader Abu Taher. Col. Jamil was arrested by the mutineers. On the same day, a group of army personnel from the 2nd Artillery rescued Ziaur Rahman (Zia) from the mutineers. Ziaur Rahman was reinstated as chief of the army. At this point, army discipline had all but disappeared, and Zia recognised the need for a firm response to maintain discipline in the Bangladeshi Army and suppress the JSD mutiny. With the forces at his disposal, Zia cracked down on the JSD, arresting Abu Taher and other JSD leaders. Abu Taher was sentenced to death and executed in 1976, whilst other leaders were given lengthy prison terms. Zia managed to bring a semblance of stability to the country and embarked on an ambitious reform programme oriented around rural development, decentralisation, self-reliance and free markets. Without antagonising Bharatiya, he began to move away from its orbit, forging ties with the United States and the Islamic world, including both the UAR and the pro-Western monarchies such as Iran, Libya and Morocco, as well as the Turkish Republic. Zia began a mild Islamicisation campaign, promoting Islam and drifting further away from secularism. By promoting Islam, he brought into the fold of Bangladeshi nationalism a number of non-Bengali ethnic groups, but this had the negative effect of alienating the Hindu Bengali community.

---

[169] IOTL such a cache was allegedly discovered in the Iraqi embassy in Islamabad. Whilst it is impossible to be certain of the veracity of this claim, the Pakistani government stated that the Iraqis were seeking to assist in the creation of an independent Balochistan that would also cause trouble for their main rival, Iran. This doesn't seem unreasonable, and as Iran is the UAR's primary rival ITTL, I'm transferring that logic to this situation.

[170] IOTL, it killed 30,000, with such a high toll blamed by Mujib on the United States, which criticised US restrictions on food shipments to Dhaka as a result of Bangladesh's sale of jute to Cuba. Without the embargo in place ITTL, there is no need for such a policy, and the food shipments should save a few thousand people.