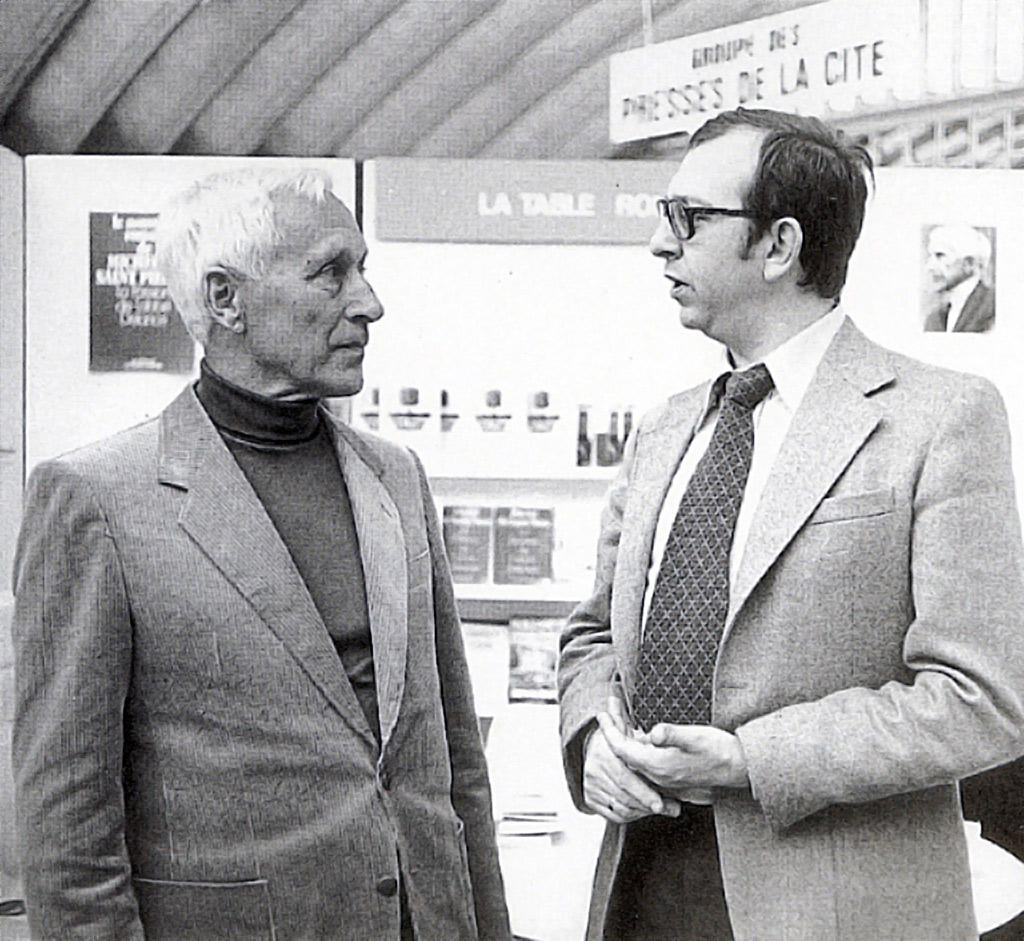

Last Badishah of Afghanistan, Mohammad Zahir Shah

Nestled amongst the mountains of the Hindu Kush, the Kingdom of Afghanistan had grown accustomed to sitting between major powers. Situated at the confluence of Persia, India and Turkestan, the region had a long and bloody history. Fought over since time immemorial, from the Achaemenid Empire to the modern day, the peoples of Afghanistan were accustomed to conflict and intrigue, both from within and without. Achieving ascendancy under the Durrani Empire, Afghanistan's frontiers gradually receded under the rule of the Barakzai dynasty, whose borders were redrawn as a result of British and Russian competition for dominance of Central Asia. Briefly coming under the British aegis, the Afghans won their sovereignty in the Third Anglo-Afghan War. Nevertheless, the Afghans had never accepted the validity of the Durand Line, an arbitrary line drawn by the British in order to separate British India from Russian Turkestan. The British would not budge from this delineation of the frontier, however, hoping to maintain Afghanistan as a buffer between their Indian possessions and Russia. This policy was continued with the success of the Russian Revolution and the consolidation of power under the Bolsheviks.

Mohammad Zahir Shah was the last

Badishah of the Barakzai dynasty, ruling over his nation since acceding to the throne in 1933. Despite temptation to take action against the British, Mohammad Zahir Shah wisely rejected German overtures to join the Axis Powers through the Second World War, as his predecessor and co-dynast Habibullah Khan had resisted German and Ottoman calls to arms in the First World War. In 1946, in the aftermath of WWII, during which the Kingdom of Afghanistan had stayed neutral, Sardar Shah Mahmud Khan was appointed as Prime Minister. Recognising the feudal backwardness of Afghanistan may have dire consequences in an era of nuclear war, Shah Mahmud Khan began to experiment with a more open political system. The results worried Shah Mahmud Khan, who worried that the proliferation of new political ideas, whether Islamist, socialist or democratic, threatened the

ancien regime in Afghanistan. From 1953, Shah Mahmud Khan was replaced by Mohammad Daoud Khan, Zahir Shah's cousin and brother-in-law. Daoud sought a closer relationship with the USSR to weaken dependence on Pakistani ties for interaction with the outside world. Disputes with their neighbour to the south prompted a temporary embargo by Pakistan and resultant economic dislocation, forcing Daoud Khan to resign. A number of politicians served as Prime Minister in the following years, but Afghan politics remained dominated by Zahir Shah.

In 1964, Zahir Shah promulgated a liberal constitution, providing for a bicameral legislature to which the King would appoint third of deputies, with another third elected by the people and the last third selected indirectly by provincial assemblies. The democratic experiment resulting from this opening of the political system (and the introduction of a political franchise for commoners) resulted in few lasting reforms, largely due to the widespread poverty and backwardness of Afghanistan. Nevertheless, it permitted the growth of the People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA). Soviet historian Alexander Tarasov[171] sought to explain the development of a radical Communist party in the feudal Afghan environment by suggesting that the lack of a "national bourgeoisie" in the form of a significant commercial or burgher class. Instead, the vanguard of the party became the relatively educated students and military officers, who sought a radical overturn of the monarchical system. In 1967, the PDPA split into two factions, the

Parcham (Banner) faction, led by Babrak Karmal, which was dominant amongst middle class students and sought a gradual move to socialism, recognising that Afghanistan was not industrialised enough to enact a genuine proletarian revolution along Marxist-Leninist lines; and the

Khalq (Masses) faction, led by Nur Mohammad Taraki and Hafizullah Amin, composed of military officers, largely of tribal extraction, who believed revolution could be achieved through the close coordination of a vanguard party and the forceful creation of the socialism. In many ways, the divide between the Parchamis and the Khalqists reflected the ongoing debate between Soviet-style Marxist-Leninism and the more radical Maoist strain in Communist parties worldwide. Throughout the 1970s the Soviets maintained contact with both wings of the PDPA, doing all that they could to prevent the tension between the two factions erupting into violence.

Mohammad Daoud Khan, first and only President of the Republic of Afghanistan

Soon the royal family were faced with corruption and malfeasance allegations in the wake of the severe 1970-71 drought. Whilst Zahir Shah was overseas receiving medical treatment, Daoud Khan seized power in a bloodless coup on July 17th 1973. Daoud abolished the monarchy, abrogated the 1964 constitution, and declared Afghanistan a republic with himself as both Prime Minister and first President. His attempts to reform Afghanistan met with little success, and despite Daoud Khan's best efforts, the new constitution promulgated in February 1977 failed to quell chronic instability. Daoud Khan had turned to repressive measures to maintain his authority, outlawing all political parties except for his National Revolutionary Party (NRP). Daoud Khan had, however, managed to quell an Islamist uprising backed by Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto of Pakistan. Many leaders of the insurrectionists were executed or imprisoned, such as Hekmatyar and Ahmad Shah Massoud, who were handed over to Daoud Khan's forces by the Pashtunistan government upon its accession to Afghanistan[172]. The Soviets remained Daoud Khan's primary backers, supporting him not only with arms and education, allowing Afghan army officers to study in the USSR, but through development, education and medical projects also. Daoud Khan sought to receive aid from the United States, which refused, citing Afghanistan's ties with the USSR. Nevertheless, the Shah of Iran and a number of Western European countries such as West Germany began to send aid and participate in development projects.

During the 1970s, despite Daoud Khan's occasional repressions, Afghanistan had begun to resemble a modern state. The campuses of the large cities were teeming with young men, beardless and wearing jeans, with their miniskirt-clad girlfriends. Kabul's skyline, whilst still dominated by the Arg and Dar-ul Aman palaces, was dotted with modern buildings sitting next to ancient bazaars and medieval mosques. But just outside of the cities, the villages of the countryside still lived by the old ways. The simple, otherwise hospitable villagers settled disputes with blood feuds, the dark side of the ancient honour code of

Pashtunwali. The attempts to drag these villagers into the twentieth century would prove the most significant challenge for the Communist forces which seized control of the government from Daoud Khan. The Khalq faction's position was strengthened by Col. Kadyr, who had participated in the coup that overthrew Zahir Shah. Kadyr established a covert group within the Afghan military, the United Front of Afghan Communists. In July 1977, under Soviet pressure, the two factions of the PDPA agreed to reunite. The PDPA elected a new Central Committee and Politburo, and appointed Taraki as their General Secretary and Babrak Karmal as his deputy. Amin's candidacy was contested. His opponents accused him of having connections to the CIA while he was studying in New York. He responded by stating that he was in dire straits financially and fed the CIA disinformation. Daoud Khan grew increasingly paranoid of the PDPA, and rightfully so. Col. Kadyr had advocated a coup, and had the support of the Khalqists. On 17th April, Parchami ideologue Mir Akbar Khaibar was murdered, either by the government or on the order of Hafizullah Amin. Khaibar's funeral saw a demonstration of tens of thousands of PDPA sympathisers. The demonstration was brutally suppressed by riot police. Daud had a number of PDPA leaders arrested, including Karmal and Taraki, on 25th April. The next day the Khalqists in the army commenced the coup. Officers sympathetic to the PDPA moved the 4th Tank Brigade into Kabul, arriving outside the Arg (the presidential palace which was also designed as an old fortress) at around midday. Troops loyal to the Khalq seized key position throughout the city, and were joined by commando forces in the evening. The putschist troops neutralised loyalist troops, liberated the PDPA leadership, and aircraft from nearby Bagram air base began bombing the Arg. That night a commando force breached the palace and demanded Daud's surrender. Refusing to lay down his arms, Daud shot and wounded their commander. The commandoes responded by slaughtering Daud and his family. Resistance in Kabul had ceased by the next morning. 43 military deaths were recorded, with some civilian casualties.

Afghan Communists marching in support of the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan

The coup presented a surprising fait accompli for the Soviets. Whilst most of the international community (understandably) presumed Moscow was behind the coup, the Soviet government had strongly promoted peaceful coexistence between the PDPA and Daoud Khan's government. The PDPA, aware that the Soviets would not approve, and fearful that they would in fact tip off the coup attempt to Daoud Khan, had launched the coup without informing their local KGB contacts. The new government immediately established a Revolutionary Council to govern the new Democratic Republic of Afghanistan (DRA). On 9th May, the new government issued a radical programme of reform. The government proclaimed as their goals the eradication of illiteracy; women's equality; an end to ethnic discrimination (the Pashtuns had traditionally been favoured as the expense of Tajiks, Uzbeks and Hazaras); a state-directed economy; and the "abolition of feudal and pre-feudal social relations" (i.e. the power of landowners, traditional leaders and mullahs). The DRA government immediately began to purge political opposition, including Islamists as well as Daoud supporters. Tribal leaders, members of influential clans and clergy were also targeted. On 15th May 1979, an uprising in Herat targeted Soviet construction workers. The men and their families were rescued from the angry mob by Afghan special forces at the request of senior Soviet military advisor Stanislav Katichev. They were flown to Kabul and housed in the embassy school until it was safe to send them back home. A handful of Soviets in the city (believed to have numbered three) were killed in the uprising, however. Amongst these dead was Maj. Nikolai Bizyukov, a military advisor with the 17th Afghan Division, who was killed in a mutiny. Amin irritated the Soviets when they contacted him demanding an explanation around the rioting and mutiny in Herat. Amin dismissed the seriousness of the situation, flippantly claiming that the governors had the situation under control. Nevertheless, Kosygin in particular was irritated at the fact that the Afghan leaders were being evasive when pressed for information about the situation on the ground. Podgorny was enraged by the gall of the Afghans, who responded to criticism of their extrajudicial killings of political opponents by stating that it had worked for Lenin and Stalin. Despite having the "situation under control", Amin requested the intervention of Soviet troops to fight increasing numbers of mutineers. When the Politburo refused, he suggested that the Soviets send tank crews with Afghan markings and staffed by Uzbek and Tajik troops. The Soviets refused, although in the end they accepted Amin's request to send military materiel and a small number of Central Asian spetsnaz units for training and specialised combat purposes.

---

[171] Alexander Tarasov is an OTL Russian Marxist academic. IOTL he hasn't (as far as I'm aware) written anything on Afghanistan, so this is a fictionalised version of him.

[172] IOTL these men would become major

mujahideen leaders supported by Pakistan. With the dissolution of Pakistan, they are unable to escape to safety and are 'gotten rid of'.